As with any great story, there’s a bit of everything in port wine history. A singular start, quarrels, alliances, scandals, tragedies, and in the end, glory. It’s ultimately the story of three countries (and many more) that in their unions and their partings created a remarkable oenological heritage.

Throughout our tours in Porto, port wine history is a recurrent theme. Our guests are often curious about this marvelous beverage and are often surprised with the twists and turns of its story. To line it out in writing seemed the best way to explain the complex history of a wine that has been around for more than 400 years.

Contents | Conteúdos

THE EARLY DAYS OF VITICULTURE IN DOURO

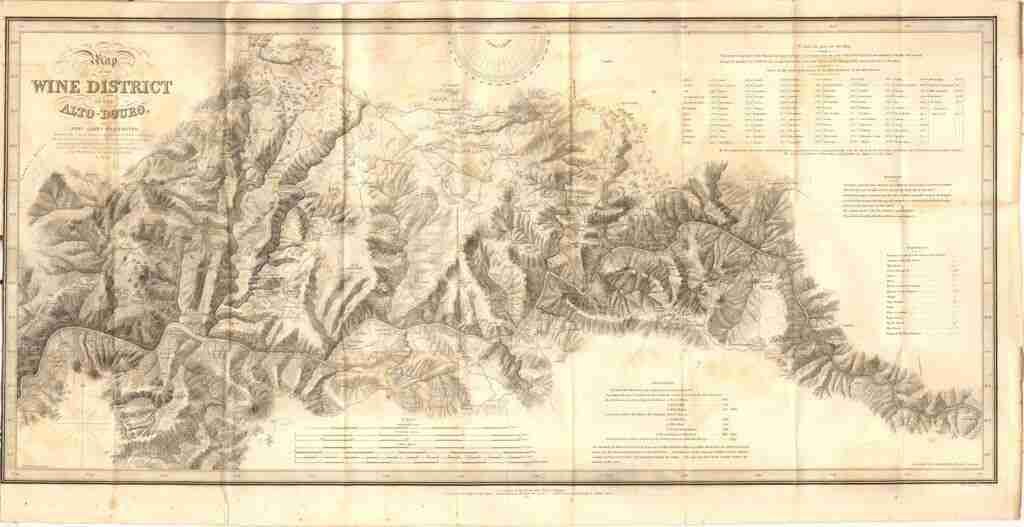

Speaking about port wine history is impossible without mentioning the region where it is produced: the Douro Valley. A territory of stunning beauty and difficult nature, that follows the countour of the river Douro since the border with Spain, in northern Portugal. A region that for centuries demanded an uncommon determination to beat the roughness of the terrain, the challenges of inaccessibility, the feisty nature of the river, and the vicissitudes of the climate. An area that is, in its own merit, the oldest demarcated region in the world.

Archaeological records show that viticulture has been present in the region since Roman occupation (2nd century A.D.), but was only widespread almost a century later. There isn’t much certainty about the state of the viticulture in the Douro during the Visigoth or Suebi reigns, but as they professed primitive Christianity, one supposed they maintained wine production, at least in order to use the wine during mass. Later on, four centuries of Arab dominion surprisingly maintained and further developed viticulture — in spite of drinking wine being forbidden to Muslims — for wine proved to be a valuable trade and export.

In fact, the historical foundation of viticulture in the Douro may have begun with the Romans, but the consolidation of the region’s wines and vineyards began only in the dawn of Portuguese nationality.

Well, you might not know this if you’re not Portuguese, but D. Afonso Henriques’ (our first king) father was Burgundian. After the early death of his father, he was raised by his faithful tutor from Lamego, Egas Moniz. It is proposed that Moniz, for strategic purposes, aided the installation of the order of the Cistercians in the Douro region, possibly also to ease the recognition of the incipient nation by the Pope. Around the year 1142, some of Douro’s four Cistercian monasteries began to pop up by order of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, also he of Burgundian origin, and a distant relative of D. Afonso Henriques.

That being said, there’s a strong probability that the Cistercian monks from the Dukedom of Burgundy were the ones to substantially develop viticulture in the Douro, by acquiring several farms, and bringing grape varieties and winemaking techniques from Burgundy.

The job couldn’t be better suited, though. After all, the work of the Cistercian monks was essential for the creation of the great French winemaking region that is Burgundy. Incidentally, it was the monks who founded the Clos de Vougeot vineyard — home of the also famed Château du Clos Vougeot — that still produces unparallel wines, in what is the epicenter of Burgundy’s best grand crus.

The main goal of the monk’s viticultural endeavor was to produce mass wine, whose purity and certain origin are essential for the liturgical act — the second goal would, quite naturally, be to provide funds for the monastery. If we observe a modern (Portuguese) mass wine, we see that it’s a sweet, fortified wine (16º of alcohol), for its fermentation is stopped with grape brandy, in similarity to port wine. This intrigues us… did medieval mass wines share the same features?

All in all, it’s undeniable that the Cistercian monks developed a major and well-organized agro-industrial activity that allowed the fixation of the population and the development of the barren Douro region. It’s almost certain that their contribute for Douro’s viticulture was of incalculable importance. And it’s very likely that their activity was the advent of port wine history.

A few centuries later, the monk’s laborious investment has fame throughout the land. In 1531-1532, the king’s foreman in Lamego, Rui Fernandes, writes an essay that describes the land surrounding Lamego. He mentions the excellent wines produced in the region, which may be aged more than 4 years, and with that aging, they greatly improve their nature. Fernandes speaks of the vineyards and of the 17 grape varieties that can be found in the vicinity. He also mentions the abundant amount of barrels produced in the region (around 15.000 barrels), and that these wines are served in the Court and noble houses, exported throughout the country and also to the kingdom of Castilla. The wines are at the time known as “vinhos de pé” or “vinhos cheirantes” (fragrant wines). João de Barros, one of the first Portuguese historians, also describes the Douro wines in his essays.

WHO INVENTED PORT WINE?

The moment of port wine’s creation escapes us. We have yet to know if it was born, or if it (more probably) grew up, as fruit of experiments through time. It’s worth looking into some of the theories that have long hung over the matter throught port wine’s history.

To begin with, we think it’s safe to say that the English didn’t invent port wine — which doesn’t mean it wasn’t fashioned to their taste.

Some authors refer that in 1678, two wine merchants from Liverpool stayed overnight in a monastery in Lamego, where the abbot surprised them with a sweet, strong, and delicious wine, to which he had added grape brandy during the fermentation, and consequently preserved some of the grape’s sugar. They were so pleased with the wine that they acquired several barrels from the monastery, which they shipped back to England.

Coincidentally, in the same year (1678), we see the first export designated as port wine (instead of Douro wine), which is undertaken by the English, who exported a total of 408 barrels. Were the barrels of the monastery of Lamego in the lot?

Be that as it may, this story contrasts with the popular notion that Douro’s wines were stabilized with grape brandy (aguardente) before shipping so it could withstand long sea travels. The usefulness of fortification is explained because increasing the level of alcohol up to a certain level reduces the activity of acetic bacteria (Acetobacter sp.), which would otherwise rapidly convert the wine into vinegar in the hot ship’s hull.

The paradox lies here: the addition of brandy to a fully fermented wine wouldn’t make it any less dry (i.e., sweeter); it would just increase its alcohol content. This means it would only be a more alcoholic table wine. And the ones that allegedly first did it to Douro wines were the Dutch (and not the English), who already had that habit regarding other “ship” wines.

So, in order for the wine to be similar to the one we know today as port wine, the addition of brandy would have to have happened during fermentation, in order to preserve some of the sugar in the grapes. Evidently, this would have to have happened during the production phase. And, at the time, the English didn’t own wine estates in the Douro; they were exclusively shippers.

Does this give strength to the theory of the Abbott, or at least, that fortifying the wine was something that winemakers already did, once in a while? That they would have further explored when requested by their clients?

This claim could be sustained with the help of the first Portuguese viniculture and winemaking treaty, “Agricultura das Vinhas (…)” by Vicencio Alarte, published in 1712, which states the following:

“In the boiling [fermentation] of the wine, it is convenient to add at least half a canada [a canada would be around 1.5 L ] of brandy per barrel, because it adds the spirits, makes the wines stronger, it is a great preparation, and in my opinion, one of the best.”

In short, the practice of adding brandy to fermenting wine would have been sufficiently generalized to appear in a viticulture treaty in 1712. It also doesn’t seem to be much of a secret that it resulted in good wine. The doubt remains, though: was there any invention? Or would this have been a relatively common and disseminated practice amongst farmers (and monks), that came to be treasured when the economic value it could add to Douro wines?

While there are no doubts that the majority of English palates favored a strong and sweet wine, the reality is that until the 19th century, most Douro wine was not fortified — they were dry and austere wines. But truth be said, there was a lot of mischief happening; the science of winemaking was still underdeveloped. We’ll talk about it ahead.

THE ENGLISH AND PORT WINE

A series of deals and commercial treaties made by the Portuguese king D. Dinis with England in the 13th-century led Portuguese merchants to trade wine, fruit, and olive oil for English wool and textiles. In the 14th-century, the Portuguese came to cover the English salted codfish, and trading it for the vinhos verdes (regional wine) from Minho.

A few centuries later, in the last years of the 16th century, the wines of the Douro supply armadas of ships that stopped (or were built) in Porto. Batches would also be shipped to Lisbon, where they would be shipped to the whole world. The more stable nature of Douro wines, also due to their higher alcohol content, made them ideal for navigation, unlike the more perishable vinho verde of Minho. By then, the viticulture in Douro was buzzing in growth to suppress the demand for vinho de embarque (ship wine).

With that change of scenario, in the reign of king Filipe II, the English merchants moved their factory house (feitoria) to Porto, progressively leaving the less profitable factory house of Viana do Castelo.

Still, the first official record of a Douro wine export to England happens in 1651, by a merchant called Richart Perez, that exported 56 barrels of wine from “above the Douro”. In the following year, other English merchants repeat the endeavor, in bigger quantities.

It’s by then that a series of English shippers start establishing themselves in Porto — the first, Newman, and then the still active Kopke, Croft, and Warre, for example.

The wine shippers established their cellars mostly in the bank of Vila Nova de Gaia, with only a few settling in Porto. This is primarily due to a strategic maneuver made by king D. Afonso III in 1255 when he gave Vila Nova de Gaia a carta foral (a royal document giving a municipality freedom from feudal control) and several benefits and privileges. This way, a lot of merchandise would be diverted from Porto, where it would have to pay a percentage in tribute to the Bishop of Porto and the Church. To avoid paying that extra tax, many shippers established their cellars in V. N. Gaia. Also, the milder climate of Gaia also proved better than Porto’s bank for aging port wine*, resulting in lighter flavors. The wine would reach the cellars of V. N. de Gaia or Porto after navigating the dangerous rivers of the Douro in the long rabelo boats. Until the 20th century, you could still find port wine cellars in Porto.

* Port wine wasn’t aged in the Douro for it gained aggressive flavors, the so-called “Douro bake”, created by the extreme temperatures of the region.

Suddenly, someone else’s misfortune came and gave a hand to the Portuguese cause, and would create a new chapter in port wine history. The growing tension between England and France had come to the boil. It resulted in an English embargo to French products (and wines) in 1678, leaving the British court thirsty for wine, and English merchants intrigued with Portugal’s potential. The traders navigate to Portuguese waters in a quest for quality nectars that would satisfy the demanding English palate.

As those who try, usually accomplish… the volume of wine barrels leaving Portugal and Porto hit a record high. However, there are those who claim that much of what embarked from Portugal to England was a clandestine sham… it was, in fact, claret from Bordeaux, the Brits’ favorite wine. How cheeky!

A few decades later, and in the context of the Spanish War of Succession, comes forth the Methuen Treaty (1703), which amongst other things gave Portuguese wines a privilege in English custom houses. The enforcement of the treaty — whose results weren’t that favorable to Portugal — drove viticulture in Portugal to a frenzy, which of course, included the Douro.

The application of the treaty soon led to a new run to supply Portuguese wine to the English table, which came with a few issues. To start, there was a scarcity of wine for such demand, and to fill in the gap and increase profit, shortcuts, and frauds appeared aplenty. For instance, some added sugar, vinho verde, or even pepper to the wine. To deepen the wine’s red hue, some added elderberries. [The use of adultering agents such as the elderberry appeared constantly throughout port wine history, at least until the 20th century] The unavoidable consequence happened: the image and prestige of port wine were deeply affected, and the outcome was a huge price drop. This calamity did not go without an answer, however.

THE MARQUIS OF POMBAL AND THE DOURO DEMARCATED REGION

Amidst mutual complaints and accusations between producers and shippers, comes the intervention of the prime minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho — later to become Marquis de Pombal — whose answer put things in shape. In 1756, the Marquis of Pombal founds the Companhia Geral de Agricultura e Vinhas do Alto Douro (General Company of Agriculture and Vines of the Alto Douro), whose goal was to recover the image of port wine, as well as regulating the production, fixing prices, and controlling (and monopolizing) its commerce and transport.

As one would expect, the creation of the Companhia wasn’t well accepted by the English and other merchants*. The problem is that they were dealing with the Marquis of Pombal: a man that was widely known to be an overpowering authoritarian.

* Neither did the tavern-owners. The Companhia controlled the commerce of wine to Porto’s taverns. As the Companhia considered that they were buying too much wine and hurting exports, they ordered the shutdown of 90,5% of the city’s taverns. The numbers fell from 1000 taverns to a mere 95! For that reason, and also because of fears of the increase of the price of wine, a popular riot broke on the 23rd of February of 1757. And as expected, the Marquis of Pombal ruthlessly punished the perpetrators — heads on spikes and all.

The English mistrust regarding the Companhia’s intentions was reflected at a diplomatic level, and the game of arguments was played from field to field amongst both countries, like a long match of badminton. It’s believed that the main fracturing issues were the fear of the loss of the English stronghold on port wine export, restrictions on the amount and season of purchases, the transport of wine in the Douro, and the monopoly in the grape brandy trade held by the Companhia.

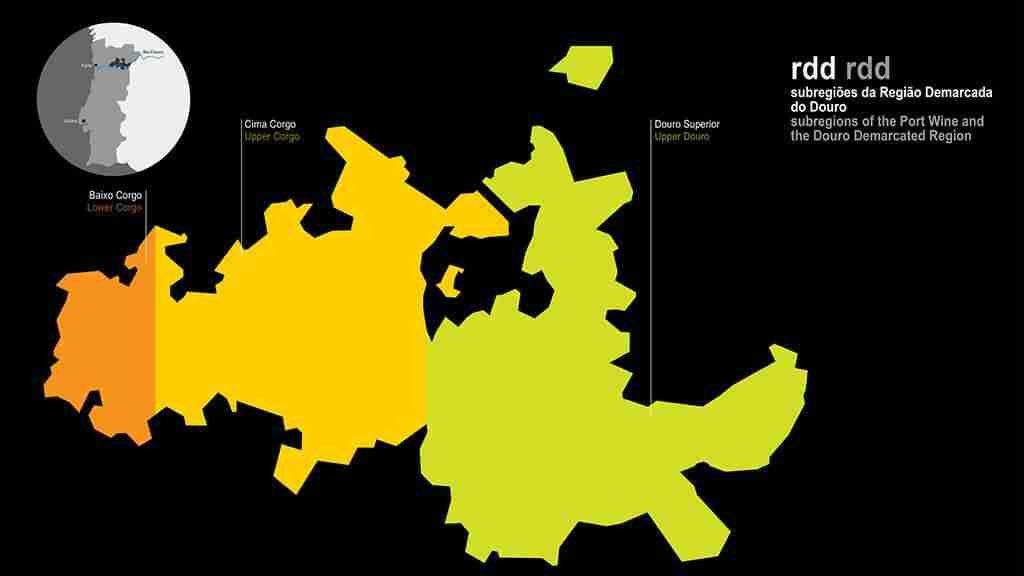

The Marquis of Pombal’s most pivotal intervention in the Douro and port wine history was perhaps the creation of the world’s first wine demarcated region. In 1756, the Douro region was thoroughly mapped and divided into two areas: one deemed for the production of wine for domestic consumption (vinho de ramo, i.e. branch wine), and the other for the production of “vinho de feitoria” (factory wine). The latter was of higher quality and destined for export, and the areas where it could be produced were delimited with engraved stone markers (factory “feitoria” markers, or Pombaline markers). Today, you can still find around a hundred factory marcs throughout the slopes of Douro, but the Douro Demarcated Region didn’t remain static. It had numerous alterations throughout the centuries, and is now quite different from 1756, as you can see on the map below.

Until then, port wine bottles were round and impossible to lie down conveniently. Consequently, with time the corks would dry out and the wine would be ruined. But here’s when something starts to change, as long and cylindrical bottles start being adopted, and those could be laid on their sides. This apparently trivial happening would come to change port wine forever, because from that moment on, port wine could be aged in a bottle, and not exclusively in casks, as it had until then. And that’s how the vintage style was born — perhaps the most glorious style of all — and the first record of one can be found in a Christie’s catalog from, referring to the 1765 vintage. Then followed the vintages from 1775, 1790, and 1797, but the system wasn’t as we know it today. The habit of declaring a vintage in exceptional harvests only began in the mid-19th-century, a practice that remains until today.

PORT WINE IN THE 19TH-CENTURY: CHANGES AND CHALLENGES

Right at the beginning of the 19th-century’s second decade (1811), the port wine sector slips into a crisis. Its main (and almost only) market — Britain — began retracting for a series of reasons. Not only the tastes of the Brits had started to change — they favored cheaper and less alcoholic wines — as some aspects of the trade conjecture between Portugal and Britain did not favor the import of Portuguese wines, and also because they started buying up wine from competitive Spain. On the other side, the viticultural sector entered a crisis due to overproduction, which led to a price fall. In the middle of this, Portugal enters a 6-year civil war. The crisis for the sector lasted until the middle of the 1860s when things started — even if briefly — looking better for the Douro.

In 1820, a most magical, most exceptional vintage occurs, one that would change the course of port wine history. It produces an extraordinary, sweet, full wine. Consumers lose their minds over this incredible vino, and so producers try to mimic it by reinvesting their interest in fortifying the wine during fermentation. Some shippers — like the prominent Baron of Forrester — weren’t partial to fortification, and thought it didn’t do justice to Douro wines. However, the clientele’s demand ended up writing the fate of port wine: it would be sweet, strong, and aromatic. And so, fortifying the wine became a general practice and paved way for the creation of the wine we know today.

PHYLLOXERA AND THE DOURO

While the Douro region was still recovering from the complicated challenge posed by a plague of powdery mildew (Oidium tuckeri) that had appeared in the 1850s – which came to be solved with the use of sulfur — there comes the most devastation bout to ever hit the region. The arrival of the phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) — a microscopic insect that feeds on the vine’s roots — to Europe in 1863 came to change the wine prospect throughout the continent. Alas, the dreadful phylloxera had been inadvertently brought by curious British botanists who had imported infected American vines from the USA. In the Douro region, the breakout also began in 1863, resulting in a fall in production in the following years. However, the phylloxera only gained full devastation momentum in the 1870s, fatally attacking the vine, and ruining wine and grape brandy production.

The efforts to stifle the ruin caused by the phylloxera were plenty, and mostly in vain. With time, European growers came to understand that the same vines that had caused the problem were also the solution. The American vine species (Vitis labrusca, Vitis rupestris, Vitis berlanderi and Vitis riparia) were naturally more resistant to the insect, thus the solution was to graft European grape varieties (Vitis vinifera) onto American rootstocks. It was a long and arduous work that eventually saved the Douro from becoming a landscape of mortórios (i.e. dead vineyards, some of which can still be seen today).

Until the 1890s, little to none English owned wine estates in the Douro. But with the devastation caused by the phylloxera, many estates switched hands at a bargain. That’s when some of the English shippers such as Graham, Roope, Warre, or Taylor started to acquire properties and investing in the replanting of the vineyards to salvage the estates.

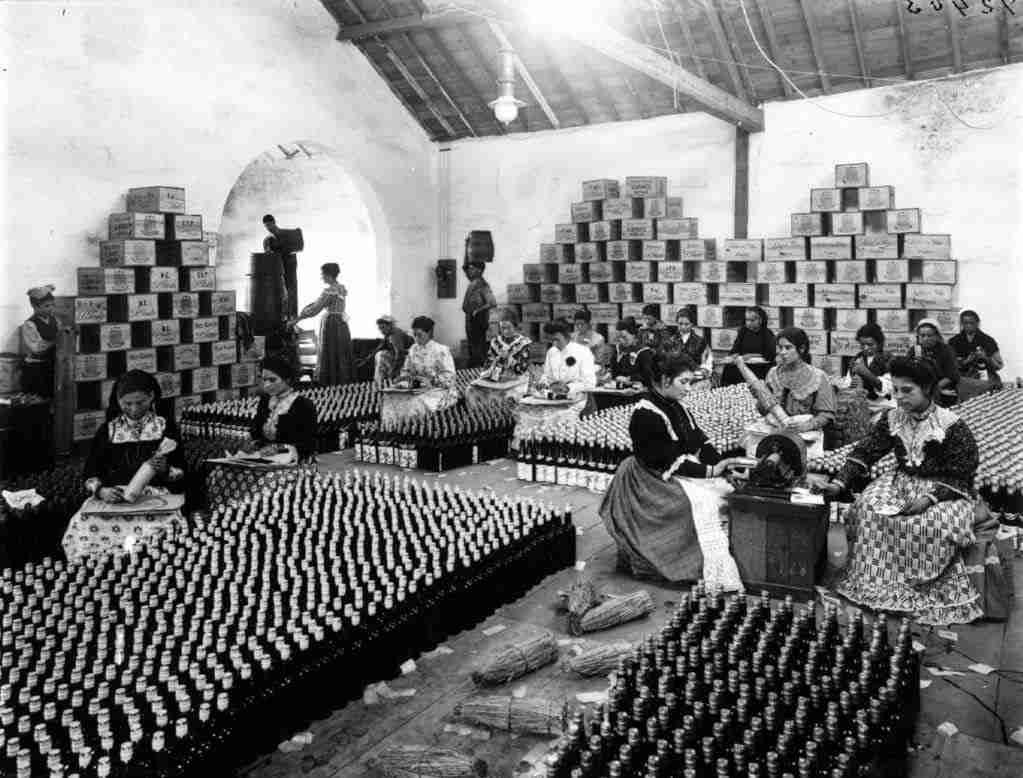

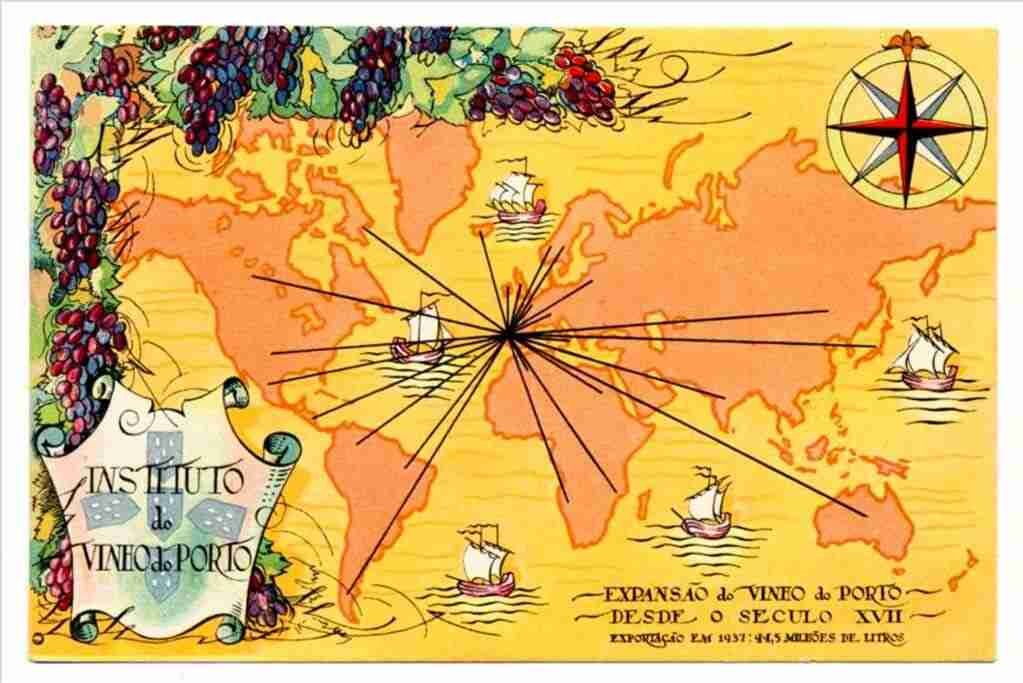

THE 20TH-CENTURY: THE ARRIVAL OF MODERNITY

The dawn of the 20th-century came with a reinforcement of port wine production, almost fully recovered from the phylloxera era. In spite of the loss of sales to the Brasilian market, port wine merchants saw an increase in demand by the French, who are until today the biggest consumers of port wine (outside Portugal). Following intense diplomatic efforts by the Portuguese state, port wine begins reaching the Danish, Dutch, Belgian, German, Swiss, American, and Norwegian markets. Nevertheless, the threat posed by the appearance of frauds and imitations — such as California “port” or Tarragona “port” — was greater than ever, as they competed in the market with low prices and equally low quality, devaluating the image of the genuine port wine. During the first two decades of the century, the Portuguese government issued several protectionist measures, as well as measures to guarantee the authenticity of the wine to the country’s that imported it.

Surprisingly, the commerce of port wine didn’t suffer a whole deal with the First World War, in spite of the ruinous state of national politics and the economy. A few decades later, with the imposition of the Estado Novo (New State, a dictatorship that grasped the country for 40 years), the Instituto do Vinho do Porto (Port Wine Institute) and the Casa do Douro (The House of Douro) are created with the goal of controlling the wine’s commerce and production in the region. But a new setback arrives: with the breakout of the Second World War, the commerce of port wine hits rock bottom, and it stays more or less that way until the 1960s. During that time, many port wine shippers closed or changed hands. But in the early 60s and 70s commerce got back on track to pre-war numbers, and grows sustainably thereon. Meanwhile, the Douro starts to change faster than ever before; aided by growth and the technological and scientific progress, the Douro we know today starts to bloom. New ways of winemaking appear, as do new styles, and new landscapes; indeed, port wine history is ever-changing. But that’s a story we’ll leave for the next chapter.

When you think about port wine, you know it to be filled with history, character, and prestige. Some will also see it as static, closed within itself, and immune to change. But in its path, port wine was at times falling into, and sometimes falling out of the market’s desires. Its medium was subjected to intense changes and new winemaking techniques. Port wine, as we know it today, isn’t the same as it was 100 years ago. It’s now a wine that is probably in its prime, be it in its production, or in the way it is presented to consumers. We must now wait to know how port wine’s history will trace its path into the future.

Celebrating port wine is above all comprised in drinking it, and protecting it. It’s curious that a drink that sparks so much national pride only saw its internal market as its biggest consumer in 2017. It’s to be known if that increase comes from avid tourists that are curious to try this incredible drink, or if it is us, the Portuguese, who have embraced it more than ever.

(some) references

Anderson, K., & Pinilla, V. (Eds.). (2018). Wine globalization: A new comparative history. Cambridge University Press.

Ribeiro da Silva, F. (2004). Os ingleses e as circunstâncias políticas do negócio dos vinhos do Porto e Douro (1756-1800). Universidade do Porto.

Cardoso, A. M. (2004). A Magna Carta da História do Vinho do Porto – A Escritura de Cister (1142). Universidade do Porto.

Pereira, G. M. & Barros, A. M. (2016) “O vinho do Porto e a Região do Douro na Época Moderna” / “Port Wine and the Douro Region in the Early Modern Period”. RIVAR Vol. 3, No 8, IDEA-USACH, Santiago de Chile, pp. 110-126.

Ludington, C. C. (2013). The Politics of Wine in Britain: A New Cultural History. Palgrave Macmillan.

Guerner, C. (1814). Discurso historico e analytico sobre o estabelecimento da Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro. Impressão Régia.

Barros, A. J. M. (2004). Vinhos da Invencível e Outras Armadas. Revista da Faculdade de Letras. Universidade do Porto

Silva, F. R. (1814). Porto e Ribadouro no Século XVII: A Complementariedade Imposta pela Natureza. Revista da Faculdade de Letras. Universidade do Porto

Alfred A Jorge

That’s a nice story but the short truth is that in order for Portuguese wine to make the trip to England and still be drinkable it needed to be fortified. So many Englishmen to on the task of producing Port, probably the reason many of the names of the great Port companies are not Portuguese.

Amass. Cook.

Hi Alfred, thank you for your comment! I guess the purpose of this post is to explain that “short truth” isn’t that clear; history proves that the idea is a lot more complex than one would believe.

Yes, perhaps the wine did have to be fortified, and fortification was an innovation created by the Dutch (you can see more about that in “Sweet, Reinforced and Fortified Wines” by Fabio Mencarelli and Pietro Tonutti), who were perhaps the first to enforce it in Douro wines around the 17th century.

Besides, the first Portuguese wines to be exported to England were the “vinho verde” wines, almost a century before Douro wines. Unfortunately, there’s nothing that tells us whether vinho verde was or not fortified (almost certainly not, though). It’d be paradoxical if you think about it, because the ABV of vinho verde is lower than the ABV of Douro wines, so they’d spoil a lot more easily. Be that as it may, it still doesn’t explain how producers started fortifying the Douro wines – during – fermentation, and not after. And that’s a completely different thing altogether: one is merely concerning biological stabilization, the other concerns a complete alteration of the wine’s structure and flavor profile, with the preservation of residual sugar.

In truth, most English companies only started producing port wine in the late 1800s, because prior to that, they didn’t own estates in the Douro. Most of the Douro wine was produced by mostly Portuguese-owned larger estates and small producers, as well as monasteries (prior to their extinction in 1834). The English company names and establishment dates, however, are often referring to their establishment as shippers, not as producers. They did buy a series of amazing quintas, and started producing at that time (e.g. Graham bought Malvedos in 1890), and have made some amazing wines since then.

You can get some insights on that on the wonderful “Port and the Douro”, by Richard Mayson. The truth is, if you look at port wine companies, you’ll see a healthy mix of companies founded or owned by people all over the world – and a lot of the great port companies are Portuguese 🙂 All in all, you can’t – and shouldn’t – take merit from the English’s dedication to and love for port wine – but things aren’t that black and white.